1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Property rights in Norway

In many ways, property rights have a special position in Norwegian society. Most citizens want to own their own property, unlike several of our neighbouring countries where in the larger cities, rental is regulated to a much greater extent so renting a home may be more financially reasonable than buying a home. Of course, such regulations will also have an impact on price development in the big cities. The capital of Oslo has seen a steady and solid rise in price development, apart from a few downturns.

Real estate is thus historically a good investment in Norway, as in many other countries.

1.2. Topic

The topic for this part of the article will be a focus on commercial real estate and property development, respectively. As far as commercial property is concerned, this will naturally include a part about rent and contract law, and for both, a relatively cursory introduction to Norwegian standard contracts and consumer housing contracts.

1.3. Sources

The sources that will be used in this text include Norwegian law, influenced by the EU consumer directive (rent) and the national standards. Property development will include both residential and commercial real estate in its general approach to the main theme.

2. PROPERTY INVESTMENT IN NORWAY

As has already been pointed out, real estate has historically made for very good investment in Norway. There are also good indications that it will continue to be a good investment in the future, especially in and around the big cities.

One of the main reasons for such continued growth may be the increasing centralization of services. The incumbent government has initiated extensive reforms by merging municipalities and in association the centralization of public services. There is no reason to believe that such centralization of public services will not lead to a corresponding decentralization in the more rural areas. If this trend continues, increased settlement and employment can be expected to centralize around the major cities, with the associated increased pressure on property prices in these areas.

However, this is much political debate, and several opposition politicians oppose the reforms and want to partly reverse them. It is unlikely this will happen, but even if it did, it would scarcely stop the social development that is moving towards densification in and around the big cities.

3. PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT IN NORWAY

3.1. The starting point – a suitable plot

Here follows a brief overview of the different stages of a Norwegian property development. Naturally, this differs from investing in a fully developed property. In many cases it is easier to start with a plot with existing buildings, demolish these and build new, or alternatively rehabilitate the existing buildings.

The alternative is to start from scratch, find a plot and develop it. With this starting point, there will be more challenges than buying a plot with buildings, but this obviously depends on the kind of project being planned.

First find a suitable plot. Initially, this will be about location. The second question is: What conditions are in place to develop the site.

3.2. What is a suitable plot?

3.2.1. Regulatory situation

The first question is what the current regulatory situation is for the property. If the property is undeveloped, it may have been set aside for various regulatory purposes in the municipal plan and area regulation, or any existing zoning plan for the specific site or area.

In domestic development projects, the regulatory situation is often the most important thing that must be clarified in order to assess whether a site is suitable for development.

However, there is no doubt that unregulated plots that can be re-regulated will have a significantly greater value-adding potential than already regulated plots. However, it is important to note that the work of regulating a site can be time-consuming and uncertain. It will be an absolute prerequisite before a purchase, that the current regulatory situation is thoroughly mapped based on the current plans, and often in dialogue with the municipality. If there is a strong desire for densification of the area, this may be a good starting point for a regulatory process.

3.2.2. The three planning levels

Norwegian planning law distinguishes between three planning levels; local planning authority (municipalities), regional planning authority (county municipalities) and state planning authority (ministry). The state planning authority involves planning at the national level and the planning tasks are listed in Section 3-5 of the Planning and Building Act. In short, these state planning tasks should not interfere with local planning, for the sake of municipal autonomy. Municipal self-government largely ensures that the municipalities can manage their areas without interfering with state actors in local political decisions.

A well-known example of such national interests is the construction ban in the beach zone (the 100-metre belt), which is statutory in Section 1-8 of the Planning and Building Act and applies throughout the country. When the regulation was introduced, it was designed to fit into all existing plans that had not already incorporated such a building ban. The consequence was that projects within the beach zone had to have an exemption, or a new zoning plan. This is also a suitable example of municipal self-government; in Section 1-8 it is clearly stated that the municipality may deviate from the building ban in new zoning plans or the area plan of the municipal plan.

3.2.3. VPOR – indicative plan

One type of plan that is more frequently used in recent years is VPOR (translated abbreviation: Guidance Plan for Public Spaces), which is a non-binding plan. Equally, in recent years, is has been demonstrated that VPOR, which is intended as a guide only, is of great importance in the development process. VPOR may be used as a direct basis when applying for a building permit.

In large cities, the use of VPOR is widespread, especially in the capital Oslo. When mapping out development areas, the use of VPOR may provide a great guidance for the municipality’s plans for the development of the areas.

3.2.4.Detailed regulation

An important tool for developers is the possibility of detailed regulation. This may be based either on the existing zoning plan or the area plan of the municipal plan, where detailed regulation proposals from the developer are submitted for a specific site.

Proposals for detailed regulation must follow the main features and frameworks in an approved area plan in the municipal plan or area-regulation. The detailed regulation should show how it contributes to the implementation of these plans. If the proposal for detailed regulation is not in line with the area plan or area regulation, the municipality may refrain from promoting the proposal on this basis. The municipality may also require that the proposer investigates the consequences of the changes the plan entails in order to take the plan into consideration.

Detailed regulation may be used e.g. in undeveloped areas that are allocated for housing purposes in the area plan, by making a proposal for detailed regulation of the land taking land distribution, road preparation etc. into consideration.

It is important to note that such regulatory tools may provide the basis for the expropriation of necessary rights, such as water and sewerage routes, roads, etc.

3.3. The construction process

3.3.1. Project

Section 20-1 of the Planning and Building Act lists the types of projects that are covered by the Building Procedure Rules. This applies, among other things, to construction, extensions etc. on buildings, façade changes, changes in use, splitting or joining of separate units in homes, significant terrain intervention, road construction, parking space, etc., and division of property.

However, not all projects pursuant to the provision are subject to an application. A distinction is made between projects that are subject to application and those that are exempt from application in the Planning and Building Act. Smaller projects may be exempt from the obligation to apply. Exceptions to the obligation to apply are described in sections 20-5, 20-6, 20-7 and 20-8 of the Planning and Building Act, including regulations (SAK10).

3.3.2. Building permit and exemption

Most projects require application and permit. Section 20-2 of the Planning and Building Act stipulates that projects subject to application cannot be implemented without an application and permit. Applications may be divided into applications for framework permits and commissioning permits, the latter being a prerequisite for commencing work.

A building permit lapses three years after the permit has been granted unless the project has been initiated, cf. Section 21-8 of the Planning and Building Act. Similarly, a building permit will lapse if there is a delay in the construction work for more than two years. However, a building permit has legal protection against subsequent planning changes within the three-year period.

If an application for a building permit is fully in accordance with the zoning plan, the applicant has a legal right to a building permit. This may be the case if e.g. there is a large property that may be divided into several properties according to the zoning plan, and an application is made for the construction of housing on the separated parcel in accordance with the zoning plan.

In such a situation, the municipality is not allowed to set conditions under a permit.

In some cases, it will be necessary to apply for an exemption from the zoning plan, cf. Section 19-1 of the Planning and Building Act. If a planned project conflicts with certain guidelines in the zoning plan, such as the height of the building, the size of the building, the number of floors etc.

Exemption under the Planning and Building Act is a discretionary assessment with two main criteria respectively; that the exemption does not substantially override the considerations behind the provision it is exempted from or the purpose of the law, and that the benefits of granting an exemption must be clearly greater than the disadvantages.

It is important to note that the exemption clause is subject to a judicial review, which means that the discretionary assessment may be reviewed by the courts in legal proceedings.

3.4. Private-law barriers for development

3.4.1. Liabilities, easements and covenants

When considering a plot’s suitability for development, it is important to consider other rights that exist on the property. After all, property rights are no more than the sum of all rights in the property, in some cases rights over the property may impose major restrictions on property rights.

In Norwegian law, a distinction is made between easements and restrictive covenants.

The easements include road rights, the right to access to a water pipe over another man’s property, etc. In short, the easements are an extended right to pursue an activity on another man’s property. There may be a distinction between a person or a property entitled to an easement. The latter belongs to a property as the dominant estate and follows the property when sold. When a person is entitled to an easement, there may be restrictions on the access to sell or inherit the easement.

Restrictive covenants condition the right of disposal of a property. There may be restrictions against noisy activities or prohibitions on a specific type of business activity. Other and highly relevant restrictive covenants are the “villa clauses”. These covenants are attached to some residential areas and impose clear restrictions on the utilization of the property, including restrictions on access to the division of the property, restrictions on the number of dwellings and size and height of the dwellings. The villa clauses are discussed separately in item 3.4.3.

3.4.2.Access and infrastructure

An absolute prerequisite for most development projects is that necessary infrastructure and road access are in place. Often this is not a problem, but in the case of undeveloped areas it may be necessary to build roads and set up infrastructure. Sometimes there may already be road access, but the existing access is unprofitable or prevents a desired use of the property.

In these cases, the developers have a few means. One of the instruments is expropriation through a zoning plan (Planning and Building Act, Chapter 16), possibly through a detailed zoning plan as described in Section 3.2.4. In these cases, the zoning plan is the direct basis for expropriation, and the expression of the balancing of interests that is a requirement in all expropriation cases. The municipality’s consent is required for expropriation in accordance with a zoning plan, and there is a time limit as the consent must be given within ten years from the announcement of the plan.

An alternative is to use the Road Act rules on expropriation of the right to use an existing road or the right to construct a new road. Pursuant to Section 53 of the Road Act, the land consolidation court (jordskifteretten) may decide on such an expropriation measure.

Expropriation under the Road Act requires a case before the land consolidation court where access to and extent of the expropriation is dealt with. The main criterion is that the expropriation is “clearly” more for “benefit than harm”. In the expropriation case the expropriator must bear the costs of the expropriation, and the process itself may thus be costly. At the same time, the compensation for expropriation will be relatively small, due to the principles of expropriation law. The background is that the sales value of areas that must be relinquished is only relevant to the extent that the areas sold have independent value. Typically, this would be the case if the expropriation meant that the person expropriated from, lost a development opportunity on his own property. In such cases it could be argued, however, that the expropriation did not do more “benefit than harm” and that alternative expropriation measures should have been considered.

In a way, road expropriation through the land consolidation court is a very suitable and useful tool for achieving the desired result. The challenge is that this process may be time-consuming, and the expropriation measure cannot be initiated until the verdict is legally valid. In theory, this means that the case may be appealed to the Court of Appeal and possibly the Supreme Court and thus it may take years before the expropriation measure can be carried out.

3.4.3.Villa clauses

As described above (3.4.1), villa clauses are restrictive covenants that may impose restrictions on development projects on a private-law basis. In areas that are known to have such clauses, developers should investigate the historical land register to determine whether such liabilities exist on the property.

If a villa clause is uncovered on the property in question, negotiations should be initiated with those entitled to the restrictive covenant.

If negotiations are unsuccessful, the developer may attempt legal measures to expropriate the restrictive covenant. The main issue being that the expropriation is “clearly” more for “benefit than harm” (Expropriation of Real Property Act, Section 2). In the capital of Oslo, restrictive covenants of this sort are quite common in central residential areas. It may be argued that the building authorities have a desire for densification of these areas, but in accordance with the practice of the county administrator and the ministry, there must be an expressed desire for densification in the neighbourhood where the restrictive covenant is to be expropriated from. A general desire for densification in the residential areas is not enough.

Another question that arises in these cases is the conflict between the restrictive covenants and current zoning plans, and whether a villa clause has lapsed as a result of a new zoning plan. According to case law, the restrictive covenant in most cases does not lapse when in conflict with a new zoning plan.

In practice from the Ministry, the decisive element is whether the restrictive covenant prevents the implementation of the relevant zoning plan. If a villa clause is a barrier for building in accordance with the zoning plan, there will be access to expropriation (case 10/1572). However, the general balancing of interests must always be considered in connection with expropriation measures.

4. COMMERCIAL PROPERTY IN NORWAY

4.1. Yield

Yield is based on the property’s cost and market value, annual income and running costs. It is calculated as a percentage based on the annual rental income divided by the property’s value; this is the gross yield. If the running costs are included in the equation the net yield can be calculated.

Yield is therefore a measurement of expected return on the property investment. It is important for the potential buyer to consider other important factors, such as the probability of finding and maintaining a long-term lessee, maintenance and infrastructure costs, and the all-important location of the property.

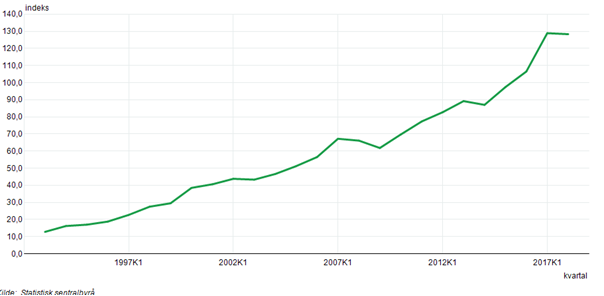

In the current financial climate we see a lower yield, especially in the largest cities. In Oslo, prime yield is currently at 3,6 %, substantially lower than a few years ago. However, there is clear optimism for the future of the commercial property market in Norway, partly because of the continuous rise in rental prices (see the graph below).

Also, interest rates are – despite recent upward adjustments – predicted to stay relatively low over the coming years. And so is the unemployment rate.

It is also important to recognize that the yield measurement does not consider the increasing property values, and hence the increased market value of the property investment over time.

4.2. Purchase of commercial property

Norwegian commercial property is usually owned through limited liability companies (LLC). The purchase of commercial property is then the purchase of shares in the LLC. Ordinarily sale of shares in another company is tax free under the domestic participation exemption.

Another advantage of this model is that the actual ownership of the property continues to be owned by the LLC. The fact that there is no change in ownership of the property means that the transfer tax of 2,5 % of the value is not applicable.

This ownership model would make it difficult to mortgage the property to finance the purchase of the shares. This problem was previously solved through a regulation (secondary law) which made an exemption from the LLC law (aksjeloven) paragraph 8-10. However, from 1 January 2020 this exemption was repealed.

It is still possible to mortgage the property, but the company will now have to follow the procedural rules in the LLC law Section 8-10.

4.3. Contracts

4.3.1. Introduction

In Norway there are several standard contracts for leasing commercial property. It is often a safe bet, especially for the lessor, to use the standard contracts. The contracts are regularly updated and revised based on case law and legal precedent.

In some cases, it may be necessary to make changes to the standard contracts regarding the specific characteristics of the rental object, or by including options in the contract. Such regulations may often be incorporated directly into the standard contract as separate provisions in a separate section, without much need for revisions to the contract as such, but this obviously depends on the change.

In the following sections we will look at a few selected topics in the design of the contract.

4.3.2.Distribution of responsibility – maintenance

The Norwegian Tenancy Act (husleieloven) Section 5-3 establishes a comprehensive maintenance obligation for the lessor. The provision is normally waived in commercial contracts where the parties agree to a different regulation of the maintenance responsibility.

The current standard contract (lease of buildings) states that the lessor’s responsibility is external building maintenance and replacement of technical facilities (elevators, ventilation systems, fire-engineering systems, etc.). The replacement responsibility does not apply to items introduced to the property by the lessee.

The lessee, in turn, shall provide and pay for the interior maintenance of the rental property, including the interior and exterior maintenance of entrance doors, gates, and interior maintenance of windows with framing, etc.

The main difference is between interior and exterior maintenance. As a rule, the lessor has no responsibility for interior maintenance, with the exception of the above-mentioned replacement responsibility for technical facilities.

It is important for the lessor to ensure a distribution of maintenance responsibility as described above, as it significantly reduces the risk of unforeseen expenses.

4.4. The Norwegian Tenancy Act

4.4.1. Standard provisions that should be derogated from

The Norwegian Tenancy Act is invariable, except for tenancy contracts regarding commercial property. There are a few sections of the law that should always explicitly be made non-applicable in the contract.

Section 2-15 in the law gives the lessee the right to withhold rent if he or she believes she has a claim against the lessor. Section 3-5, 3-6 and 3-8 have rules on the lessee’s deposit or payment guarantee. Usually these sections should be made non-applicable because professional parties in a commercial contract will make their own agreement on deposits or guarantee.

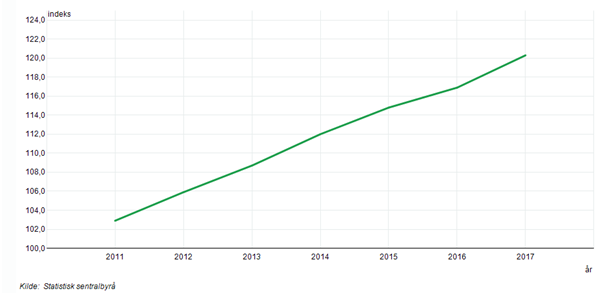

Section 4-3 gives the lessee the right to adjust the rent to the current level of rents a few years into the contract. The usual practice when leasing commercial property is an annual adjustment of the rent in accordance with the Norwegian consumer price index. Other indexes are also applicable, which can give better security for the lessor for price and market fluctuations.

Section 5-4 first paragraph and 5-8 first to fourth paragraph is usually made non-applicable, because the first section restricts the lessor’s access to the property by requiring consent for work on the property of some significance. The second section regulates compensation for damages and restricts the access to compensation.

Section 7-5 regulates the lessee’s right to sublet. This access should be restricted in a commercial contract. Sections 8-4, 8-5 and 8-6 regulates the lessee’s right to transfer his or her tenancy rights to a third party and change ownership to the lessor. These sections are usually made non-applicable and replaced with special regulations, which partly limits the lessee’s right to transfer his tenancy rights.

Section 10-5 gives the lessee the right to compensation for improvements on the rental object unless the parties have agreed otherwise. In contracts regarding commercial property the length of the contracts are usually up to 20 years, and Section 10-5 would create difficult situations at the end of the rental period, partly because of the lessee’s obligations to maintain the rental object.

In some contracts (not the current standard contracts) the parties agree to render Section 12-2 non-applicable. The section gives both the lessee and lessor the right to demand a rent evaluation board to judge what is correct market rent for the rental object. In some cases, it may be in the lessor’s interest to limit the lessee’s right to a rent evaluation board, because it gives them a better negotiating position when the rent is due to be regulated.

4.4.2. Dispute resolution

Dispute resolution in commercial rental contracts may be handled through arbitration, legal proceedings or a rent evaluation board as described above. Should the parties want to handle dispute resolution through arbitration this can be agreed upon in the initial contract, as well as making Section 12-1 non-applicable. In other instances, the parties may agree on voluntary arbitration if desired and dispute resolution through arbitration is not agreed upon in the contract.

4.5. Housing-contracts

Housing rental contracts are regulated in full by the Norwegian tenancy act, which is invariable in these contracts. The Norwegian consumer council have standard contracts for tenancy agreements.

It is important to be aware that there was recently passed regulations to restrict short-term letting of apartments. The main aim of the regulation is to prohibit apartment hotels, but it also applies to private individuals. The regulation limits the total number of days an apartment may be let out short-term. The limit is set to 90 days per year.

This means it is no longer profitable to own apartments based on an Airbnb or similar short-term rental business model. The time of implementation for the new regulations is 1 January 2020.

5. NORWEGIAN STANDARD CONTRACTS

5.1. Building and construction contracts

The Norwegian standard collection includes several legal standards for the construction industry. These contracts are available in both Norwegian and English.

The legal standards (general conditions) available in English include:

- Contract for design commissions (NS 8401),

- Contract for consultancy commissions with remuneration on the basis of actual time taken (NS 8402),

- Contract for construction supervision commissions (NS 8403),

- Norwegian building and civil engineering contract (NS 8405),

- Simplified Norwegian building and civil engineering contract (NS 8406),

- Contract for design and build contracts (NS 8407),

- Contracts concerning the purchase of construction products (NS 8409),

- Contract for sub-contracts concerning the execution of building and civil engineering works (NS 8415),

- Simplified contract for sub-contracts concerning the execution of building and civil engineering works (NS 8416),

- Contract for design and build sub-contracts (NS 8417)

The general conditions in the contracts are to some extent considered non-statutory law, which means the contractual obligations in the general conditions of a Norwegian standard contract may be applicable even if the standard is not agreed upon. This has its obvious limitations, especially as it is possible to deviate from the standards.

5.2. Consumer contracts

The legal standards described above may only be used between two professional parties. If the project is to build a house for a private individual, and this individual is the contracting party, the act relating to contracts with consumers on the construction of private dwellings (bustadoppføringslova) is invariable.

In Section 3 of the Act it is regulated that the contractor cannot agree or apply contractual conditions that gives the consumer less protection than what is stated in the Act. This does not mean that it is unnecessary to have a contract with the consumer. The conditions in the contracts will be applicable to determine what has been agreed upon between the parties and then conclude which rights the consumer or contractor have in regard to the Act.

A good example of this is the regulations in the act that determine when a consumer may demand to take possession of the house, i.e. when the construction must be completed. If the contractor has not specified a time for the take-over or completion time, or just made vague indications, the consumer cannot demand to take over the property. This means the consumer cannot either demand a daily fine or time penalty if the construction period exceeds the estimates. However, a time estimate needs to be realistic at the time of the contract. Otherwise, the Supreme Court concluded, negligence on the contractor’s part regarding time estimate, may lead to claims for compensation and time penalty.

Pål Gude Gudesen

Partner